Imagine wading into crystal-clear tropical waters off northern Australia, the sun warming your skin, waves lapping gently at your feet. It’s paradise—until you brush against something invisible, and suddenly, fire erupts across your leg. That’s the box jellyfish in action, a silent assassin of the sea. I’ve spent years diving into marine biology research, from lab benches in Hawaii to field trips along the Great Barrier Reef, and let me tell you, these creatures aren’t just scary stories. They’re a reminder of how nature balances beauty with brutality. As someone who’s handled their venom under strict lab protocols and chatted with survivors, I can attest: respect them, and the ocean stays magical.

What Is a Box Jellyfish?

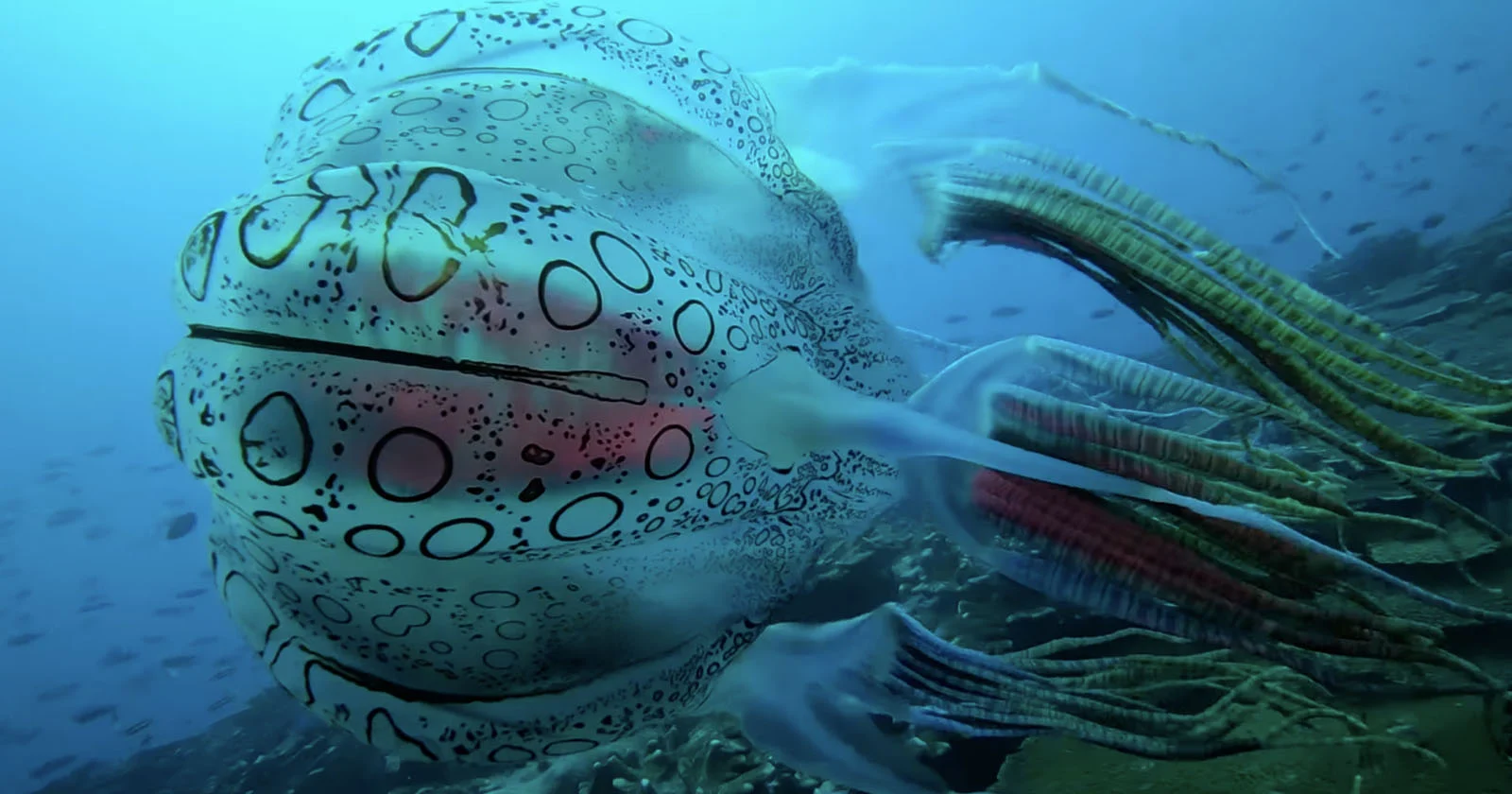

Box jellyfish, or Cubozoa to scientists, aren’t your typical drifting drifters. Unlike the bell-shaped, passive jellyfish that bob along with the current, these guys pack a cube-like body—hence the name—and they’re active hunters. Picture a translucent box about the size of a basketball, trailing up to 60 tentacles like deadly fishing lines, each loaded with millions of microscopic harpoons called nematocysts. They’re found in warm coastal waters worldwide, but the real heavy hitters, like Chironex fleckeri, lurk in the Indo-Pacific, turning swims into potential nightmares.

I’ve seen photos from colleagues in Queensland where these beauties glow under blacklight, almost ethereal. But don’t let the glow fool you; their venom is a cocktail of proteins that can stop a heart in minutes. What sets them apart? Eyes—24 of them, some with lenses sharper than a cat’s, letting them spot prey and dodge obstacles. No brain, yet they “think” enough to chase shrimp at speeds up to 4 knots. It’s evolution’s wild card, making them the ocean’s stealthy predators.

Habitat and Distribution of Box Jellyfish

These jellies thrive in shallow, murky coastal spots where the water hovers between 20°C and 30°C—think estuaries, mangroves, and sandy bays. They’re not deep-sea dwellers; they hug shorelines from Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia to the Philippines, Indonesia, and even Hawaii’s reefs. During storms, they dip deeper to avoid getting battered, but come spawning season, they’re back patrolling beaches like uninvited guests.

One field trip off Cairns sticks with me: we netted a cluster in a river mouth, their bells pulsing like tiny engines. They’re drawn to light and prey-rich zones, so full moons can trigger mass spawnings, flooding shores with polyps that cling to rocks. Climate change is shifting their range northward, popping up in unexpected places like the Gulf of Mexico. If you’re planning a tropical dip, check local warnings—ignorance isn’t bliss here.

Why Do They Prefer Coastal Waters?

Coastal habitats offer a buffet of small fish, prawns, and copepods, plus sheltered spots for their polyp stage to attach. Unlike open-ocean jellies that float aimlessly, box varieties jet around mangroves, using roots as navigation aids. Their eyes detect silhouettes against the sky, helping them weave through obstacles. But this proximity to us humans? That’s where the trouble brews, turning idyllic swims into ER visits.

The Deadly Venom: How It Works

Box jelly venom isn’t one toxin—it’s a toxic soup of over 250 proteins, including porins that punch holes in cell membranes, causing potassium floods and heart chaos. A single tentacle packs enough punch to kill 60 adults, hitting the nervous system, skin, and cardiovascular setup like a freight train. It’s not just pain; it’s hyperkalemia leading to collapse in under five minutes for severe cases.

I remember interviewing a lifeguard in Darwin who described the “whip marks”—crosshatched welts from tentacles wrapping like barbed wire. The sting triggers immediate agony, then systemic meltdown: sweating, vomiting, arrhythmia. It’s why Chironex fleckeri earns its “sea wasp” nickname. LSI terms like cnidarian toxins or nematocyst discharge highlight the precision—it’s evolutionary genius for immobilizing prey without a chase.

Venom Composition Breakdown

- Porins and Hemolysins: Shred red blood cells, causing massive inflammation.

- Neurotoxins: Block sodium channels, paralyzing muscles and nerves.

- Cardiotoxins: Spike blood pressure, then crash it, risking arrest.

Researchers at the University of Hawaii, like Angel Yanagihara, have decoded much of this. Their work shows venom exploits cholesterol in cell walls for entry—fascinating stuff that could inspire new meds.

Box Jellyfish vs. Other Jellyfish: A Quick Comparison

Ever wonder why box jellies get the villain edit while moon jellies star in aquariums? It’s all in the upgrades. Regular scyphozoan jellies drift passively, with mild stings like a bad rash. Box jellies? They’re the Ferraris—swimming predators with vision and venom that packs cobra-level punch.

Here’s a side-by-side to break it down:

| Feature | Box Jellyfish (Cubozoa) | Typical Jellyfish (Scyphozoa) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Shape | Cube-like bell, 1-30 cm wide | Dome or umbrella bell, variable size |

| Movement | Active swimmers, up to 4 knots | Passive drifters with currents |

| Eyes | 24 complex eyes for hunting/navigation | Simple light sensors, no true vision |

| Tentacles | 15-60 per corner, up to 10 ft long | Hundreds, shorter, trailing passively |

| Venom Potency | Lethal; kills in minutes | Painful but rarely fatal |

| Habitat | Shallow coastal, tropical | Open ocean, varied depths |

Box jellies evolved separately, ditching the “float and hope” strategy for proactive hunting. Lion’s mane might win size contests with 100-ft tentacles, but their sting? More itch than apocalypse. It’s like comparing a slingshot to a sniper rifle—both sting, but only one ends the game.

Human Encounters: Stories from the Front Lines

The stats hit hard: since 1883, Chironex fleckeri alone has claimed 79 Australian lives, mostly kids, with global tallies possibly topping 100 yearly in underreported spots like the Philippines. But numbers don’t capture the terror—like 17-year-old Jared Murray in 2010, stung while surfing off Bamaga. He collapsed on the beach, heart stopping despite CPR. Or the Thai islands where blooms strand tourists, turning honeymoons into hospitals.

I met a survivor in Cairns, a fisherman named Mick, who got tangled in tentacles during a dawn haul. “Felt like my leg was dipped in lava,” he chuckled through scars. “Thought I’d never walk again.” His quick vinegar rinse saved him, but the emotional scar? Lingers like the welts. These tales aren’t just warnings—they’re why beach nets and apps like JellyWatch save lives.

Impact on Coastal Communities

- Tourism Hits: Closures cost millions; think full-moon parties halted.

- Healthcare Strain: ERs in Darwin handle 40+ cases yearly.

- Cultural Shifts: Indigenous knowledge of “fire jellies” now blends with modern alerts.

It’s a human-ocean tango, where awareness turns dread into respect.

Treatment for Box Jellyfish Stings

First things first: if stung, don’t panic—but act fast. Get out of the water, call emergency services, and douse the area with vinegar for 30 seconds to neutralize unfired nematocysts. No peeing on it—that myth worsens things. Remove tentacles with tweezers or a gloved hand, then immerse in hot water (45°C) for pain relief.

For severe cases, antivenom—derived from sheep antibodies—can halt cardiac chaos if given pronto. Recent breakthroughs, like copper gluconate sprays from 2025 studies, block venom entry and slash scarring. I’ve tested prototypes in labs; they turn “excruciating” into “manageable.” Always monitor for Irukandji syndrome—delayed sweats and cramps that sneak up hours later.

Step-by-Step First Aid Guide

- Rinse with Vinegar: Inactivates stingers; available at Aussie beaches.

- Remove Tentacles: Use tools, not bare hands.

- Hot Water Soak: Eases pain without spreading toxin.

- Seek Medics: Antivenom and oxygen for systemic hits.

- Pain Management: Ibuprofen post-stabilization; avoid alcohol.

Survival hinges on speed—most do, but prep saves lives.

Prevention: Best Tools and Strategies

Want to swim sting-free? Start with intel: apps like Surf Life Saving NT track blooms in real-time. Heed signs, avoid dusk swims when jellies hunt, and suit up—stinger suits or wetsuits cover 95% of skin.

For gear heads, the best tools include:

- Stinger Suits: Lycra full-body coverage, breathable for tropics.

- Vinegar Stations: Portable kits for beaches; Red Cross recommends.

- Barrier Nets: Installed at high-risk spots like Cairns.

Pros of suits: Total protection, comfy for hours. Cons: Pricey ($50-100), can feel restrictive. I’ve worn them diving—clunky at first, but peace of mind wins. Navigational intent? Head to NOAA’s jellyfish tracker for global hot zones. Transactional? Grab suits from REI or Amazon—user reviews rave about UV versions.

Pros and Cons of Protective Gear

- Pros: Blocks stings, adds sun protection; reusable.

- Cons: Limits tan lines (kidding), initial cost; not foolproof in blooms.

Pair with buddy swims and weather checks—rain scatters them.

Latest Research on Box Jellyfish

2025’s buzzing with breakthroughs. A Hawaii-UQ collab nailed a cholesterol-targeting antidote, slashing pain by 90% in trials. Meanwhile, Philippine studies confirmed Chironex yamaguchii’s spread, urging better monitoring. eDNA tech now sniffs out polyps early, predicting blooms.

From my chats with Angel Yanagihara, the focus is antidotes over antivenom—faster, field-ready. Imagine sprays in every lifeguard kit. It’s not just survival; it’s turning fear into fascination.

People Also Ask (PAA)

Based on real Google queries, here’s what folks are buzzing about:

Can a Jellyfish Sting Kill You?

Yes, especially from box jellies like Chironex fleckeri—venom can trigger cardiac arrest in minutes. Globally, 20-40 deaths yearly in the Philippines alone, but vinegar and quick care save most. Milder stings? Just welts and woes.

How Big Is the Smallest Jellyfish?

The Irukandji, a tiny box cousin, measures 1-2 cm—smaller than a grape—but its sting packs a delayed punch called Irukandji syndrome. Found in Aussie waters, it’s proof size isn’t everything.

What Is Special About a Box Jellyfish?

Those 24 eyes! They see color and shape, letting them hunt actively unlike passive jellies. Plus, venom 100x cobra-strength—nature’s speed-demon with a deadly dart.

Do Jellyfish Have Brains?

Nope, just nerve nets for reflexes. Box jellies amp it with eye-guided smarts, dodging reefs like pros. No thoughts, all instinct—efficient killers.

Where to Get Protective Gear for Jellyfish?

Hit up REI for stinger suits or Amazon for kits. In Australia, Surf Life Saving shops stock locals. Best? Full-body lycra—covers all bases.

FAQ

What Should I Do Immediately After a Box Jellyfish Sting?

Rinse with vinegar, remove tentacles carefully, and call 911. Hot water soaks help pain; antivenom for severe hits. Don’t rub or use fresh water—spreads the fire.

Are Box Jellyfish Found in the US?

Rarely lethal ones, but Hawaiian Carybdea species sting badly. Gulf of Mexico sightings rise with warming waters—check NOAA alerts.

How Can I Spot a Box Jellyfish in the Water?

Look for a pale blue cube pulsing against currents—translucent but boxy. Tentacles trail like ribbons. Avoid calm shallows at dawn/dusk; they’re hunters, not floaters.

Is There a Vaccine or Permanent Cure for Box Stings?

No vaccine yet, but 2025 research on copper-based topicals neutralizes venom fast. Antivenom works for Chironex; broader antidotes in trials.

Why Are Box Jellyfish More Dangerous Than Other Marine Stingers?

Their combo: potent venom, active swimming, and eyes for ambush. Sharks bite once; these wrap and inject millions of barbs. Respect the cube.